Phoenix Robot Digs into Martian Soil for First Time

NASA'sPhoenix Mars Lander has successfully stretched out its robotic arm to scratchat the Martian soil for the first time, mission scientists said Monday.

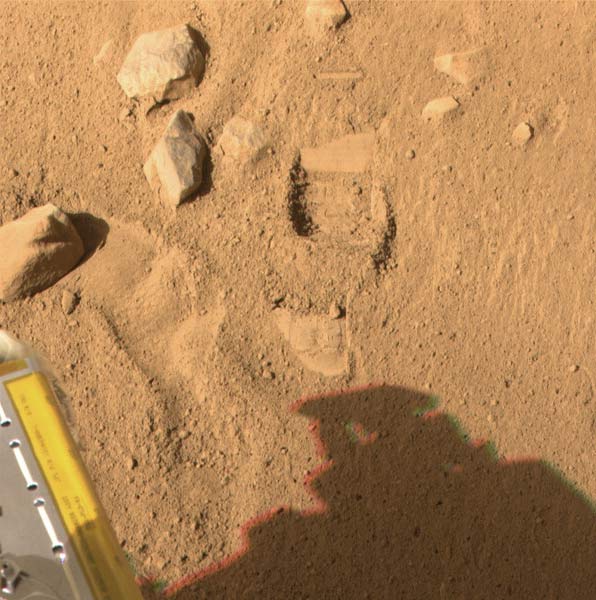

Phoenixperformed the test dig Sunday in a spot just above a dent left by the scoop ofits robotic arm when it first touched the soil on May 31. Researchers dubbedthe dent "Yeti" because of its strong resemblance to afootprint.

Touchingthe soil and performing this so-called "dig and dump" are the firstpractice steps toward digging up soil samples and delivering them to theinstruments on the lander. The instruments aboard the$420-million spacecraft are designed to analyze the soil and underlyinglayers of water ice to see if the ice was at some point liquid and whether itcould have created a habitable zone for microbial life.

Phoenix not only scooped up and dumpedmaterial on the Martian surface, it also snapped a photo of the stuff in itsback hoe-like maw.

"Thesoil is crumbly and there's also some light-toned bits," said RayArvidson, the robotic arm co-investigator of Washington University in St. Louis.

These"light-toned bits" were also seen in the trench left by the scoop."We got very excited because we see this nice streak of whitematerial," said Phoenix senior engineer Pat Woida.

Whatexactly the white material is is uncertain, though Arvidson proposed one of twopossibilities.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

First, thewhite material could be salts that formed while liquid water was present.Second, and more tantalizing, the stuff could also be part of the underlyingice layer similar to the smoothbright regions spotted under the lander in photographs, which missionscientists also think could be iceexposed by the thrusters as the craft landed. Researchers christened theodd regions ?Snow Queen? and ?Holy Cow.?

"Wewere so excited about it we called it Holy Cow," Arvidson said.

The successof Sunday?s practice dig and dump means that the team can focus on the nextstage of Phoenix's mission: sampling and analyzing the soil.

"Thatwas all very, very successful, so I don't think we need to do any moretesting," Arvidson said.

The team iscurrently scouting for new dig sites, which will likely be three side-by-sideareas (one for each of the lander's three analysis instruments), which the teamplans to name "Baby Bear," "Mama Bear" and "PapaBear." The dig targets will likely be just to the right of the test dig,where Phoenix?s 7.7-foot (2.3-meter) robotic arm can easily reach.

The teamhas gone back to their original plan of delivering the first sample to thelander's Thermal and Evolved-Gas Analyzer (TEGA), which heats up samples andanalyzes the vapors they give off, after a glitch over the weekend has beenworked out. A filament in part of the analyzer shorted out, but missionengineers have found that they can use a second, back-up filament to do theanalysis with the same amount of sensitivity.

Missioncontrollers will look at the data from Phoenix's downlink on Monday night andif the TEGA covers have fully retracted, "then TEGA will be good togo," Arvidson said.

NASA?s Phoenix Mars Lander toucheddown in the Martian arctic on May 25 to begin a planned three-month missionstudying the surrounding terrain, weather and searching for water ice.

- Video: Sounds From Phoenix Mars Lander's Descent

- New Images: Phoenix on Mars!

- Video: The Nail-Biting Landing of Phoenix on Mars

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.